Equal to the task: why is there a lack of women in culinary competitions?

There's no battle of the sexes when it comes to chef competitions; although men frequently take the top spot, female chefs are failing to even reach the judging stages. Vincent Wood asks whether it's a question of bias or a lack of opportunity

The hospitality industry is in the midst of an overdue culture shift when it comes to women in kitchens. Role models like Core's Clare Smyth and Darjeeling Express' Asma Khan are making pioneering steps, both in their food and their approach to life behind the pass. Long-held calls for a removal of the hyper-masculine era of kitchens are being answered, albeit slowly. However, in the nation's top culinary competitions, women still appear to be underrepresented.

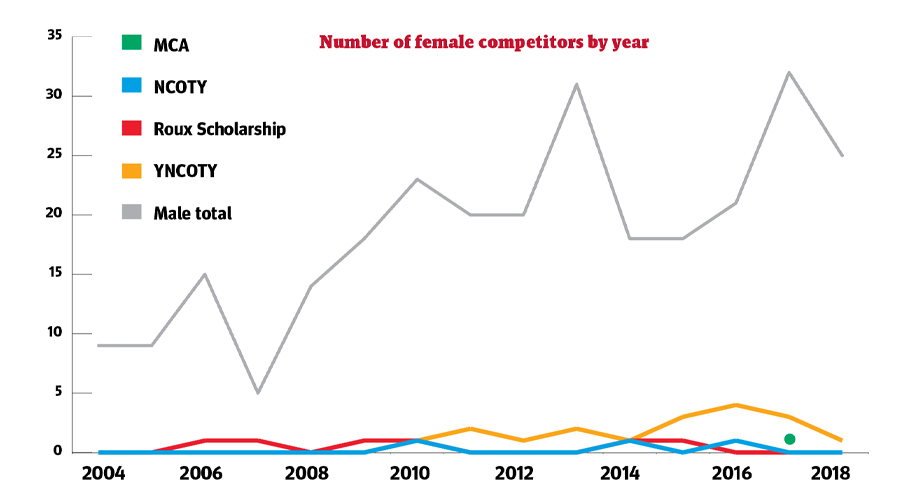

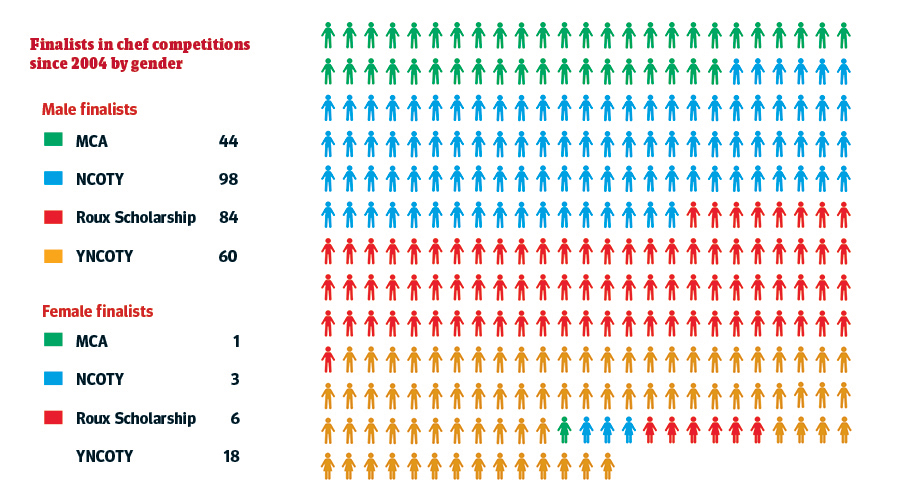

Between 2004 and 2018, 314 finalist spots were available in the industry's most elite culinary competitions: the Craft Guild's National Chef of the Year (NCOTY) and Young National Chef of the Year (YNCOTY); the Royal Academy of Culinary Arts' Master of Culinary Arts certification (MCA); and the Roux Scholarship. Analysis by The Caterer has found that of those 314, only 28 places were taken by women, with just 22 reaching the final in the last 14 years.

While this could be a reflection of the number of women in the industry in relation to their male counterparts, the numbers are still diminished when compared to female competitors and female chefs in the workplace. Since 2004, women have made up an average of 30% of hospitality workers, but only 8% of top-tier competition finalists.

ever many industry figures approached by The Caterer believe the number of female chefs rising to prominence through elite tests of culinary brilliance is the tip of an iceberg. Year-on-year, fewer and fewer women are remaining in the industry, and too few are rising to senior positions. In 2004, 45% of chefs in the workforce were women according to the Office for National Statistics. In 2018, that number had declined to 18%.

he 32 Masters named in the history of the competition for cuisine or pastry have been female (Claire Clarke and Yolande Stanley, both pastry chefs).

Stanes said the figures were: "absolutely not due to any gender bias in judging, but simply a reflection of the industry as a whole", noting that the RACA's other accolades come closer to gender parity - such as the Annual Awards of Excellence, which has had 32% female winners since 2005. She added: "Looking at this senior level across the industry, the fact is that there is a greater proportion of male professionals to female."

Her sentiments are shared by Monica Galetti, who made her name as the first female senior sous to serve in Le Gavroche, London, before opening Mere in Fitzrovia. She said: "It is possibly a representation that echoes the number of women chefs in the top end of the industry - and it is at the top end of the industry where these skills to cope in such top competitions are taught."

eed, real growth can be seen in the Craft Guild's YNCOTY, with its natural focus on lower level chefs. While women made up 3% of finalists in the senior competition since 2004, 23% of young chef finalists have been female since the competition's inception in 2010: 18 female finalists - more than the Roux Scholarship, NCOTY and MCA achieved in 14 years, combined.

Galetti, who also serves as a judge for NCOTY, added: "Mere has only been open two years and it's only now I am able to focus on training up one or two of my chefs to enter in the future. They have come a long way, but still have more to learn before they are ready."

NCOTY organiser and vice-president of the Craft Guild of Chefs David Mulcahy believes being thrown into the deep end of elite culinary competitions can provide a training ground of its own. He said: "Chef competitions in general have always been more popular with male chefs; this is something we are keen to address as a NCOTY team.

"While female chefs are currently under-represented in culinary competitions, being part of NCOTY offers so much more than a title or a finalist spot. From personal growth to being part of a fantastic community of like-minded chefs, there are so many opportunities for career and personal development, whatever stage of the competition you get to."

haps the proof that dwindling numbers could be more systemic than a matter of direct bias is that the disparity is also evident in blind competitions. The Roux Scholarship has had one female beneficiary since its inception, and since 2004 has had six female finalists out of 90 competitors (not including the seventh, Claridge's Olivia Catherine Burt, who competed in the final last month).

Entrants are selected without names - or indeed indications of gender - attached to their submissions, judged only by the quality of their recipes. This year the number of female entrants overall rose slightly, to 6%. Michel Roux Jr said: "We agree that the number of female chefs getting through to the finals is disappointing, but the issue is the lack of representation across the industry. We all need to do more encourage young women into this amazing career, following such inspiring chefs as our judges Clare Smyth, Rachel Humphrey and Angela Hartnett."

Continue reading

You need to be a premium member to view this. Subscribe from just 99p per week.

Already subscribed? Log In